Pink Laptops are patronising.

In tIn this edition we talk with Dr Rain Ashford who specialises in researching and creating wearable technology. We talk about her passion for state of the art technology, aesthetics and research.

Tell me about what you do

I'm a wearable technology designer, technology project manager, user experience researcher, consultant and educator, for which I combine my knowledge and experience of working with hardware, software, and design. I’ve spent many years in the technology industry working in research and development, broadcast media and also in academia. I enjoy working on the cutting edge of new technology and most recently, AI and machine learning. My PhD focussed on the design and construction of responsive and emotive wearable technology research prototypes and exploring the requirements of potential users. I investigated the possibility of how wearable technology could be used to create new forms of non-verbal communication using a gamut of sensors to collect physiological data from the wearer, including EEG (electroencephalogram), ECG (electrocardiogram) and GSR (galvanic skin response), proximity, temperature and more, with which I amplify and broadcast as sensory feedback, such as visualisations of data, sound or haptic feedback.

EEG prototyping with electronics and programming, image © Rain Ashford

How did you become interested in technology?

My introduction to computing was through playing games on my older brother’s computer, which led me to become interested to discover what else I could do with it. My mum and I sat with the user manual and we typed in the commands to create an animation. Initially, we made a lot of mistakes and typos but kept hacking at the code until it worked. This was my first foray into programming.

What was your first job in tech?

It was designing and building websites and games for an agency in London, mostly for shopping carts and campaigns. A year later I moved to the BBC as I was more interested in creating educational and entertainment driven media such as games, videos and tutorials, plus support material for live TV and Radio broadcasts. I became interested in how technology was marketed through conducting UX sessions for interactive media websites, educational games and content. Research led me to interview people from various demographic groups, some didn’t have online access or help with digital literacy, and their stories revealed how they had found technology inaccessible and user manuals intimidating. They often found it difficult to ask for advice and so got stuck deciphering the language or iconography used in instructions for common home appliances such as TV remotes, cameras or get to grips with technology to get online, such as routers or using services such as online banking. Around the same time I was seeing a lot of patronising marketing for technology aimed at women, such as pink coloured technology for laptops and wearables, plus apps with domestic themes such as recipe finders. This pushed me to investigate aesthetics for wearables as part of my PhD research, to find out how people, especially women, would really like their technology products to be presented.

Presenting at OpenTech Conference on wearable technology, image © Rain Ashford

Do you feel the world has moved on much since then?

I don’t know if it has, really, but it feels like I talk to more people who are generally aware and informed. I think UX is better structured towards inclusion and design for all, but there are still problems with stereotypes that creep in. You can see it being ingrained from a young age in toys and clothing, for young girls reflected in pastel pink and purple passive cuteness and slogans, whereas boys are dressed for action in strong blues and greens with superhero imagery.

What is the work you have done that you are most proud of?

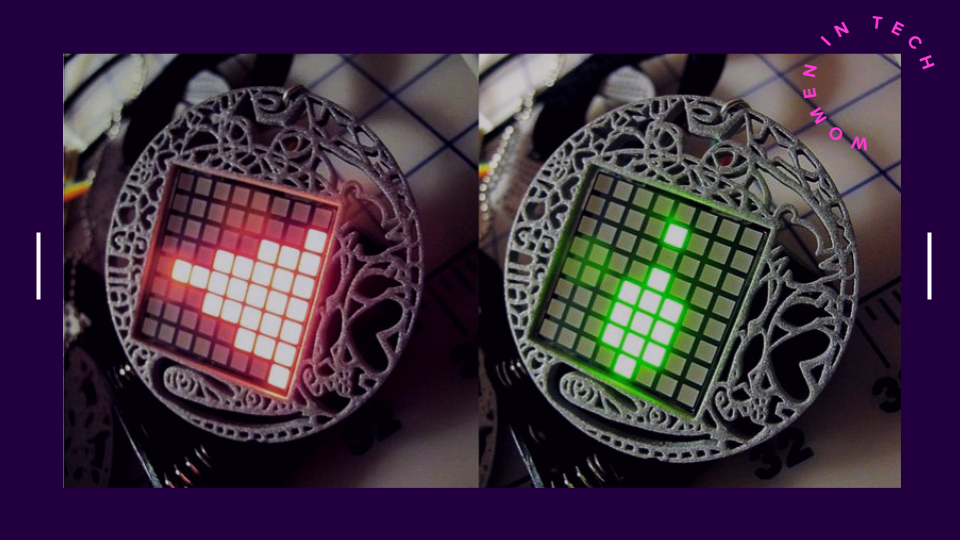

I’m most proud of my work in wearable technology and PhD research. Particuarly, that I was able to push myself to learn skills in programming, engineering and design. Moreover, to put my knowledge together to create wearables that might in the future help people think about how we use technology on the body or how we express ourselves and communicate. For example, I created a dress that visualises the wearer’s EEG attention (concentration) and meditation (relaxation) data. It came about from user testing sessions with different groups of women where we discussed their functional and aesthetic requirements of wearable technology. One idea that came out of this focussed on difficulties in communication in noisy environments such as in a bar or a club. The fibre-optics on the dress, which are woven into organza, map levels of red (attention) and green (meditation) light to visualise EEG data. It would be used as an aid to keeping in touch with friends in a crowded environment, as even from a distance you would be able to interpret if the person wearing the dress might be in an uncomfortable situation and needed help or intervention. This dress is an example of how we can use wearables for non-verbal communication or as a secret language of colour and light between the wearer and onlookers who know how to interpret the light patterns. It illustrates how physiological data can be used for safety and communication in environments where it might be harder to signal for help. The dress is a research prototype that I have exhibited around the world. There are many companies working on safety-related wearables and I hope my research can help inform and inspire other designers.

Thinkerbelle EEG dress, image © Rain Ashford

You entered the world of tech through art & design?

Design has always been of interest to me. Early wearable technology was very clunky, made from bits of huge old computers as there just wasn’t suitable components available. Due to the miniaturisation of technology such as sensors and actuators we’re now able to either hide the tech inside something aesthetically pleasing or we can use the look of the technology to create a new aesthetic. Everyone is different and one size doesn’t fit all in terms of how we want to look and be viewed. This applies to the design of wearable technology too, as of course what you wear on your body becomes part of your persona. In my user testing sessions, some participants said they wanted their wearables discrete and hidden because they would feel self conscious about wearing something as prominent as an EEG headset, which is understandable, but others were totally happy with the aesthetics of technology visible to all. I’ve walked around London and other cities wearing EEG headsets and my wearables to discover what the experience is like, whether people stare, and to see if you feel confident or intimidated. I’ve found it an interesting experience as eye-catching prominent technology on the body wasn’t and still isn’t the cultural norm. For example, a design issue around the observer’s gaze came up when I was designing and testing my EEG visualising pendants. If you are wearing such technology on your chest to broadcast data in the form of a pendant then that’s where people’s eyes will be drawn too, and some field trials participants unsurprisingly felt uncomfortable about this. Wearers also found that if someone they are talking to is constantly looking at the pendant, it takes away eye contact. These observations opened up a can of worms in terms of the repercussions of how we will wear technology on our bodies now and in the future.

EEG Visualising Pendant , visualises attention (concentration) data as red patterns and meditation (relaxation) data as green patterns, image © Rain Ashford

Where are we in this journey and what will it look like in 10 and 20 years?

The wearable technology market is being currently being driven by health and wellness, combined with the opportunities that AI and machine learning bring for areas including monitoring and diagnosis. There are still a lot of questions to ask about usage of our data and datasets in AI/machine learning in terms of areas such as underrepresentation, bias and data security as it becomes embedded in our everyday life. This has led me to become involved in discussion around responsible AI and AI for good, which I hope can mitigate some of these fears. I hope in the future AI will be used for good in terms of aiding health infrastructure and give people to access health services and diagnostic tools. Wearable technology of course cannot yet replace a consultation with a doctor, but it could help people monitor changes in their health and aid diagnosis.

Interview on wearable technology for BBC Outriders, Television Centre, London, image © Rain Ashford

What’s your main bit of advice for young women looking for a career in tech?

Don’t be put off by feeling you are the odd one out. Research your area, think about what interests you about technology and what you might achieve from it. Don’t be put off if you don’t know in the beginning exactly where your path will lead you, because through time, experience and experimentation your preferences will become clearer. Working in technology is not a piece of cake, but the rewards make it worthwhile. You have to study quite hard and not let other people put you off or stop you from following your instincts, but by believing in yourself you can do it! Learning skills in technology might seem hard from the outside, but working hard and chipping away at problems will steer a path towards a career that suits you and you will enjoy.